“I don’t even think he can see that he’s actually kind of violent. You don’t have to push too far to think about what not hearing ‘no’ means.”

– Professor Claudia Johnson; Murray Professor of English Literature at Princeton University

I came here to edit this into a real piece, but the fact that it’s silly and repetitive and messy—and a way to reason out an answer to the ideas I thought were mistaken on a podcast that contributed so much to my education and appreciation of Jane Austen—makes it untouchable. This mess is an artifact. And as I was about to cut out and rewrite the most embarrassing parts directly responding to that podcast, I paused long enough to remember that those same women referenced me and my writing on their last episode, and thankfully I stopped myself in time. So fine, I wrote this stupid thing six months ago that makes me feel foolish now, but as this was the first thing I ever wrote about Jane Austen, it’s a precious kind of foolishness. This was the start of something pure and joyful that I never imagined or looked for, and changing it would be like destroying a scrapbook of Baby’s First Steps.

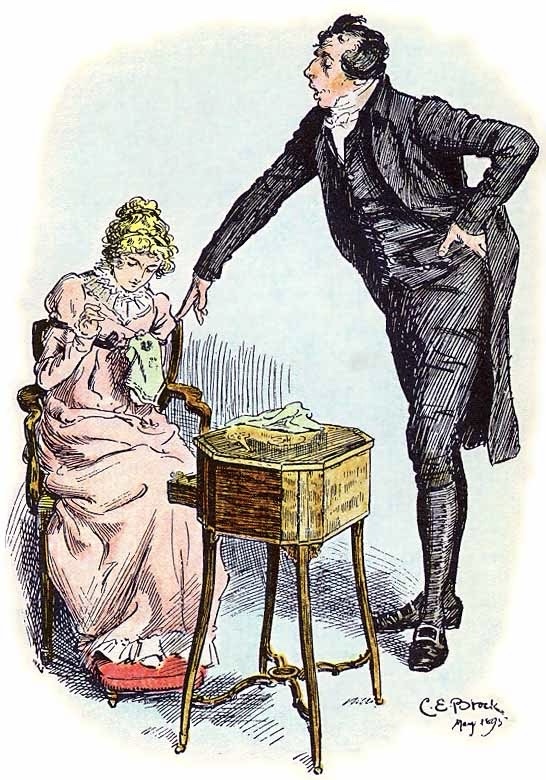

Mr. Collins completely dehumanizes women from his first moment on the page to his last. In his proposal to Lizzy he is not charming or sweetly stupid, he’s the root of all evil to all women in history. The evidence doesn’t become unavoidably explicit until his letters about Lydia, but it was right there in front of us all along.

Mr. Collins is at bottom, a hateful, resentful man who dehumanizes Lizzy and her sisters continually. Poisonously abusive in every way, he wears a pastor’s frock instead of a tank top.

Collins is a particular type of clergyman that we know more about today, and it dazzles me that although Austen could not know the full extent of what this sort of church man’s dark sins would be, she drew him as if she did. Mr. Collins would not be the man abusing the altar boys, he would instead be the man covering up for the ten men who did. He wears the frock to have power over people who would otherwise not give him the time of day, particularly women.

He wants to make the women around him feel small.

The tendency towards that type of abusiveness shows in his no-questions-asked “proposal,” in his pleasure at holding his cousins hostage to read obnoxious injunctions at them in their own livingroom against their will on how to be submissive, and of course comes out more expressly in his later letters celebrating the punishment he expects to befall Lizzy and her sisters from Lydia’s elopement, including his admonitions to cut her off forever.

He is close to as big a piece of $#*+ as Wickham is, but Mr. Collins has a much longer reach.

Austen’s Insidious Poisoners

Mr. Collins’ is a very specific type of Jane Austen antagonist that she reshapes and brings back to life again in “Mansfield Park,” “Emma” and “Persuasion.” I’ve come to think of these creations as Insidious Poisoners. They tend to be at least a little funny and—except for Aunt Norris in “Mansfield”—may even have traits the reader empathizes with. I don’t think that Mrs. Elton (“Emma”) sets out to be a horrible person, but besides being one of the funniest characters ever written, she is foolish, shallow and self-involved enough to cause plenty of thoughtless harm. She is, like Mr. Collins, Aunt Norris, and to an extent the elder Elliots, an undeniably corrosive social force in need of mediation that Miss Austen obviously recognized and drew from life. These Austen antagonists all have two things in common: one, they want to see our heroine fail, and two, they will get their well-deserved comeuppance in the end without any evil act of another’s. They are masters of their own fates. They will all choke on their own poison. And meanwhile, they give us an extra boost of satisfaction from the final triumph of our beloved precisely because they wished, from the bottom of their petty little souls, for her failure.

And of all these petty and venomous souls I believe Mr. Collins is the worst. He is unquestionably the most insidious. Aunt Norris is awful, no doubt, but her relative powerlessness and lack of disguise limit her sting. Mrs. Elton is funnier than she is hateful, and Emma’s marriage is probably enough to make her behave. But Mr. Collins, though stupid, has found himself adjacent to power and is shameless enough, careful enough, and obsequious enough to do real damage. His obsequiousness, I think, is his secret weapon. As camouflage it surpasses sheep’s clothing, as it is nearly unimaginable to think someone so imbecillically servile could also possibly be dangerous.

“Dear ma’am, do not go. I beg you will not go.”

– Elizabeth Bennet; “Pride and Prejudice,” Chapter 19

A resentment-fueled spider and his No-Questions-Asked proposal

He won’t take “NO” for an answer, but then again, it wasn’t a question.

I always want to put “proposal” in quotes, because Mr. Collins never bothers to ask anything. He speaks nonstop of his happiness and Lady Catherine, drowning Lizzy in a flood of words which only stop when she finally interrupts him. Her answer is superlative, just like she is.

But for simplicity’s sake we can keep calling it a proposal.

- To me the proposal, which even before it starts Lizzy wants to “escape” from, feels like a man pinning a woman down and refusing to get off until she cries “uncle.”

- And even after Elizabeth is able to escape, and when thanks to Mrs. Bennet, Mr. Collins finally realizes that the “no” was serious, what soothes him? That Elizabeth will get the reproach of her mother for what he terms “her behavior.” His comfort is that someone else will hold her down and make her feel small in his stead.

This began in my Notes app when I realized, to my horror, that some people found Mr. Collins kind of sweet. He might be silly and sad, but he’s trying to do the right thing. And one thing they pointed to as support for that view is that Lizzy is so relatively polite to him. Compared to her evisceration of Mr. Darcy, she is practically complimentary to Collins. But Elizabeth is in an impossible situation that requires her to operate within more formal bounds than she needs to with Darcy. For me, these invisible strictures only increase the intense suffocation of this scene.

Her mother has ordered Elizabeth to hear his proposal and Lizzy understands that Mrs. Bennet wants her to accept it. Mr. Collins is her cousin and in this room where she is trapped with him by the chains of familial duty she must act in a way that does not dishonor her mother or father. The straitjacket is invisible, but real. The very fact that she feels she cannot “escape” because it is wrong to disobey her mother’s explicit orders gives her all the reasons she needs to be polite—though she struggles to stay so. She simply wants this over with, but she is also representing the family in a very real way, is aware that her mother will already be unhappy with her, and she wants it over with the least damage possible. Unlike Mr. Darcy who will “quit the house” after it’s all done, she will have to keep seeing Mr. Collins, and existing side-by-side with him and the rest of her family together.

I don’t think we need impart any internal feelings of goodwill onto Lizzy as a motive for minimizing the damage as much as she can. But that necessity she feels increases the claustrophobia of the scene. It makes her desire to escape more palpable to me, and it makes the fact of her refusals causing him to be more and more insistent especially reprehensible.

“No ungenerous reproach”

Jane Austen has Mr. Collins reveal his true colors by contradicting himself in words or deeds, over and over again. After vowing that he will never bring up Lizzy’s lack of fortune when they’re married, he turns around and does just that before he has even accepted her rejection; as proof of why she can’t afford to turn him down.

The last thing Collins gets out in his proposal before Lizzy says her first “no”:

“To fortune I am perfectly indifferent, and shall make no demand of that nature on your father, since I am well aware that it could not be complied with; and that one thousand pounds in the 4 per cents., which will not be yours till after your mother’s decease, is all that you may ever be entitled to. On that head, therefore, I shall be uniformly silent: and you may assure yourself that no ungenerous reproach shall ever pass my lips when we are married.”

It’s perhaps the nicest thing he says to her in the whole monologue.

But as they are not yet married it takes no time at all before he throws that very “ungenerous reproach” in her face as one of the reasons her “no” will not even be heard by him.

“… you should take it into further consideration that, in spite of your manifold attractions, it is by no means certain that another offer of marriage may ever be made you. Your portion is unhappily so small, that it will in all likelihood undo the effects of your loveliness and amiable qualifications.”

“Hey, I’m doing you a favor, here. You think anyone else is going to take you?”

So like every other seemingly nice thing he says throughout the entire book, he didn’t mean it. But he said it. Beggars can’t be choosers, after all. It’s the signature Collins triple play: preening in his borrowed power, flattering himself, and belittling Elizabeth. As always, a belittling wrapped up and arranged as a kindness to her and a compliment to him.

Just like his cruelest letters are packed with knives arranged as care and empathy, so they are unexpected and cut deeper. “I’m writing to rejoice in that brat who silenced me’s misfortune and yours, so I will get my condolences out of the way quickly and tell you that it’s all your fault and by the way, tell Lizzy she got what she deserved and haha I escaped it.”

I feel myself called upon, by our relationship, and my situation in life, to condole with you on the grievous affliction you are now suffering under… The death of your daughter would have been a blessing … is the more to be lamented, because … licentiousness of behaviour in your daughter has proceeded from a faulty degree of indulgence…

My dear Sir,

“Dear sir, I am writing to tell you how sorry I am that your daughter is not actually dead…”

Can anyone believe that he meant the nice things wrapped up in knives early in the book, but not the ones later in it? That his cruelty is a new affliction?

And for the record, not being heard, not being seen, trying to communicate with someone who just wants to smother whatever you are and instead pretend you don’t exist and play your part for you, as if that’s good enough because you’re just a stand-in anyway, that is so uniquely difficult. In ways that are hard to express and that the usual articulable terms of expression cannot quite describe, but that feels indescribably awful even in normal circumstances. And this is not a normal circumstance. This man would legally have power over Elizabeth, and until she can get away he has power over her now and will not hear her. Her mother who has legal and moral power over her wants to hand that power to him, and in this moment this man can control her, yet she doesn’t exist to him. The first time I read Lizzy basically begging Mr. Collins to see her as “a rational creature speaking the truth from her heart” — trapped in her own dining room and begging to be seen, begging to be heard—only to have Mr. Collins respond with, “You are uniformly charming,” I burst into tears. Tears I didn’t understand at all, but felt with my whole soul.

I have learned a lot and love the “Reading Jane Austen” podcast. I often agree, sometimes disagree, and occasionally vehemently disagree. On Mr. Collins, it’s simple: Ellen is wrong. Here, I’ll show you. Don’t worry, it’ll be fun. (•◠‿◠)︎ノ

❈︎ Ellen revised her views once she thought of those last Lydia letters, she just tends to start with a generous view of people and that’s something I can’t fault her for.

Answering Ellen from “Reading Jane Austen”:

__〆( ̄ー ̄ )

Spotify link starting at the quote:

ELLEN: I found myself sort of admiring Mr. Collins. He’s so determined to do the right thing, you know, and he’s worked it out that in terms of the old sorts of marriage proposals, he’s doing the right thing in keeping the property together, keeping the family line going. If he marries one of those girls then he will have done his duty by the property.

HARRIET: Yes.

ELLEN: And he’s sort of quite dignified when he says to them, “I’m sorry about that.” And when Mrs. Bennet is saying, “I’ll get her to do it,” him saying, “No,” he doesn’t really want that.

I feel certain I am going to change your mind.

Point by point:

1. Doing the right thing on keeping the property together and the family line together:

Does he really care about doing the right thing? Is that his motivation in this, or his motivation in anything? I’m not seeing it. Even in his first letter where he says how “highly commendable” his “present overtures of goodwill” are before mentioning his “concern”— that concern only extends to Mr. Bennet’s amiable daughters.

“I cannot be otherwise than concerned at being the means of injuring your amiable daughters…”

Funny, that. But then again, I’ve never seen a drop of evidence that Collins cares about anything but power and looking pious. He was told to go get himself a quick wife, and where else was he going to find one?

It is not said explicitly that Lady Catherine pointed to Longbourne as Mr. Collins’ hunting ground, but it is strongly suggested by her sending him off to find a wife and telling him to “bring her to Hunsford.” She must be “brought” because she is elsewhere, and what “elsewhere” is there? Where else but Longbourn and the cousins whose beauty and amiability he had heard about could Mr. Collins have any hope of popping into for a fortnight and coming out with a fiancé?

“…thirdly, which perhaps I ought to have mentioned earlier, that it is the particular advice and recommendation of the very noble lady whom I have the honour of calling patroness. Twice has she condescended to give me her opinion … she said, ‘Mr. Collins, you must marry… This is my advice. Find such a woman as soon as you can, bring her to Hunsford, and I will visit her.’”

And for what it’s worth, I don’t buy for a second that he had “many amiable young women” in Hunsford to choose from. We well know from Elizabeth’s visit to Charlotte that “the style of living of the neighbourhood in general was beyond [his] reach,” to begin with and that his social calendar was all Lady Catherine, Lady Catherine, and Lady Catherine.

Their other engagements were few, as the style of living of the neighbourhood in general was beyond the Collinses’ reach.

What fits with every part of his character displayed throughout the book, alongside what we can see for ourselves about the general ridicule he attracts from everyone not female, middle-aged, and of a lower class, is that not only would he have very little chance with women on an equal footing with him, but that he was well aware of this and also liked the idea of having a woman who started out in his debt. Someone he felt couldn’t afford to reject him and who would come into the relationship owing him.

He prefers (and exploits) power imbalances.

Both he and Charlotte accidentally landed in each other’s way—and because he was feeling desperate and she wasn’t in any way in his debt—they also landed into a fortunate situation where they have relatively equal power. (Excluding the inherent gender power asymmetry.)

Lastly, if all that isn’t enough, Jane Austen does for us with Mr. Collins what she will not do for us with Mr. Wickham: She warns us in her Austenisms about what he is and how to view his intentions in words so thick with sarcasm they’re almost gooey.

…in seeking a reconciliation with the Longbourn family he had a wife in view, as he meant to choose one of the daughters, if he found them as handsome and amiable as they were represented by common report. This was his plan of amends—of atonement—for inheriting their father’s estate; and he thought it an excellent one, full of eligibility and suitableness, and excessively generous and disinterested on his own part. His plan did not vary on seeing them. Miss Bennet’s lovely face confirmed his views, and established all his strictest notions of what was due to seniority…

It’s almost as if Austen knows we might miss the genuine reprehensibility of Mr. Collins, so she really emphasizes it. And I think this is what she has Lizzy judge Charlotte so harshly for. Not because Mr. Collins is silly, but because he is a poisonous person. Conceited. Narrow-minded.

“Mr. Collins is a conceited, pompous, narrow-minded, silly man…”

That she also calls him “silly” should not distract us from the incredibly strong language she chooses to describe how Lizzy views Charlotte’s choice to chain herself to him.

“You shall not, for the sake of one individual, change the meaning of principle and integrity, nor endeavour to persuade yourself or me, that selfishness is prudence, and insensibility of danger security for happiness.”

Danger. That’s the word she chooses. And I’ve always thought, “That’s a bit much,” and have judged Elizabeth incredibly harshly for how she judges Charlotte, but in writing this and in spending several days really studying Austen’s drawing of Mr. Collins, I now see this plot point differently. I think it is very little about Charlotte marrying for “the wrong reasons” —an opinion which Lizzy will repent of later—and very much about telling us again that Mr. Collins isn’t just a ridiculous character meant to entertain, he is also poisonous. The way Lizzy describes him, even this early, is like he’s actively harmful. (And I think she’s right.)

2. The dignity he exhibits when he tells the girls he’s sorry that he’s inheriting the property.

I cannot ever find Mr. Collins’ character dignified, but as an opinion I have a soft spot for Ellen finding it so. I sense something good in her when she says it. Especially at this point, because if he meant it, it would be only right to admire him for displaying empathy in this way. What I will say is that I find Mr. Collins insincere and his words meaningless based on his conduct in the rest of the book, and his own testimony.

This is a man who sits around thinking up “elegant compliments” for the most shallow and self-adulatory reasons, reasons that have nothing to do with the supposed objects of his false flattery.

“…though I sometimes amuse myself with suggesting and arranging such little elegant compliments as may be adapted to ordinary occasions…”

He “amuses” himself by thinking up and “arranging” words he does not at all mean to kiss the ass of a powerful woman, because that woman can increase his power. Which is why the main service he provides to his parishioners is finding out dirt on them and running to Lady Catherine with it so she can scold them. (Although I’m sure to earn these poor people’s trust he says very nice words to them, too.)

3. He tells Mrs. Bennet that he doesn’t want her to force Lizzy to accept him.

Certainly during the proposal he intended to get Mr. and Mrs. Bennet to force Lizzy as far as the law allowed. After she has told him “no” FIVE times in the most explicit terms the English language provides—“impossible,” “perfectly serious,” “matter finally settled,” “know not how to express my refusal”—he shows his utter contempt for her by saying:

“and I am persuaded that, when sanctioned by the express authority of both your excellent parents, my proposals will not fail of being acceptable.”

And after he saw Mrs. Bennet and he started to feel the sting of rejection, did he “change his mind” because he didn’t think she could contribute to his felicity, or was he deeply offended and his fragile pride injured? Either way, even after he technically backed off from the attempt at trying to use her parents to force her, he still wanted her parents to punish her.

And this is exactly how he acted about the Fordyce’s Sermons and Lydia, too. When Lydia (heroically, in my opinion) interrupted his forcing on them of these misogynistic lectures and the three eldest Bennet women scolded Lydia and asked him to continue, he was very injured and “offended,” and refused to continue reading.

(This sets up his clear dislike of Lydia, too, which he will get to rejoice in later.)

I think this scene is very important because it is an example of Mr. Collins holding these women—whose future loss of Longbourn he is professing to feel sorry about—hostage. In Longbourn. Just like he holds Lizzy hostage in the proposal scene.

When he says he never reads novels and is clearly going to refuse to read the book he has been invited to read to his captive audience, “Kitty stared at him, and Lydia exclaimed.” So he cannot be unaware of their feelings on the matter. But he has the power and intends to force himself on them. Force his will on them. I struggled with this wording because of the obvious sexual connotation, but although I don’t mean it sexually, I always put myself in the sisters’ place when I read this and feel myself not far from hyperventilating at the thought of him exerting his power to keep me still and silent as the reprehensible windbag delights in being able to force feed me whatever he likes.

Lydia was bid by her two eldest sisters to hold her tongue; but Mr. Collins, much offended, laid aside his book, and said,— “I have often observed how little young ladies are interested by books of a serious stamp, though written solely for their benefit. It amazes me, I confess; for certainly there can be nothing so advantageous to them as instruction. But I will no longer importune my young cousin.”

But to him changing his mind about asking Mrs. Bennet to force Lizzy, he is already taking rejection as we’ve seen him take it before and as he will again, by being offended and resentful, and despite deciding against dragging a headstrong woman kicking and screaming into marriage, he does hope to see her scolded for her refusal.

…the possibility of her deserving her mother’s reproach prevented his feeling any regret.

Think about that. That’s cold. It is so easy to miss how unfeeling he is. How the only emotions he tends to rejoice in are the most base and selfish ones.

Then Austen reinforces his duplicitousness and lack of genuine character again right after the proposal when Mrs. Bennet [tries] to send everyone out of the room to talk to Mr. Collins about Lizzy’s refusal.

Collins vows not to resent “the behavior” of Lizzy. (“Behavior” is such a telling word. As if there was something immoral in making the choice to refuse his proposal that deserves punishment. And it shows, again, that he believes consent to be unnecessary to a man in his position. It does not matter if his cousins want to listen to him read an offensive book to them in their own home, and it is wholly irrelevant that Lizzy does not want to marry him—“your refusal of my addresses are merely words of course”—words that don’t count because they are not his. What Collins changes his mind about is whether it’s worth the time and trouble to force a woman into marriage who is going to keep bothering him by having—and worse, expressing—feelings and opinions.)

I got sidetracked on “behavior” when I meant to focus on how Austen uses “resentful” so artfully after the proposal.

“My dear madam,” replied he, “let us be for ever silent on this point. Far be it from me,” he presently continued, in a voice that marked his displeasure, “to resent the behaviour of your daughter…”

Then Austen markedly uses that exact adverb—“resentful”—to describe his reaction just two pages later:

As for the gentleman himself, his feelings were chiefly expressed, not by embarrassment or dejection, or by trying to avoid her, but by stiffness of manner and resentful silence.

“Pride and Prejudice” ❦ Chapter 21

And in case you missed that Collins was a false character whose professions are never to be believed and whose character is not to be trusted, Austen tags him with it again just three sentences later:

Mr. Collins was also in the same state of angry pride. Elizabeth had hoped that his resentment might shorten his visit, but his plan did not appear in the least affected by it.

“Pride and Prejudice” ❦ Chapter 21

We will discover later in his letters about Lydia that he is a bad guy and not just a silly one, but Austen has been giving us the clues all along.

One last thing that really twists the knife for me is that in the post-proposal conference with Mrs. Bennet after his, “Well, I really didn’t want her anyway” speech, he apologizes for taking the refusal from Lizzy’s lips — (which of course he didn’t) — and for not asking them to “interpose [their] authority” to try to force Lizzy to marry him.

“You will not, I hope, consider me as showing any disrespect to your family, my dear madam, by thus withdrawing my pretensions to your daughter’s favour, without having paid yourself and Mr. Bennet the compliment of requesting you to interpose your authority in my behalf. My conduct may, I fear, be objectionable in having accepted my dismission from your daughter’s lips instead of your own; but we are all liable to error. I have certainly meant well through the whole affair.”

Again, what he thinks he did wrong was listening to the woman he had wanted to become his wife. The woman he just proposed to by not asking her a single question and whose unqualified negatives were “just words, of course.” “No” is meaningless to him from her, and even objectionable. Bad “behavior,” worthy of punishment. What he did wrong, what he is apologizing for is, first, his after-the-fact pretense of accepting her “no,” and second, for not asking her parents to try to force her into total submission to his will.

How are we—how is anybody—making excuses for a man whose whole character is based on refusing to listen to the outright, unqualified “NO” of every woman he has any power over? And worse, a man who believes to the tips of his toes that those women have no right to oppose him, that his desire is their duty, and that opposition to his will is, in every case, in-and-of-itself wrong.

Missing evil because it is cloaked in clergy robes and meaningless words has done more harm to more innocents than all the serial killers put together could ever do. In Pride and Prejudice we have two villains. One is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the other is a spider masquerading as a fly.

Mr. Collins is not a good guy. Or even a neutral but harmless fool. Mr. Collins is poison.

So many of the character traits he pretends to possess are repeatedly held up by Austen and shown to be a lie, and if we were not distracted by his flurry of obsequious and exonerative words, we would more easily notice Austen constantly telling us that he is doing the opposite of what he says.

Mr. Collins is a weak, resentful, immoral man who feeds his power kink by humiliating women like the ones who laughed at him his whole life. The borrowed authority of the clerical perch is just a vehicle for him. He has no real morals, and his boot-licking does not show a desire to do the right thing, but only a misguided way to seem pious without developing real character. “Look at me, I’m moral, if I do say so myself.” Jane Austen shows us how shallow his words are by the repeated examples of his words being almost immediately contradicted in the text by the narrator, or him immediately giving the lie to them himself when his original script doesn’t go as planned.

4 Comments Add yours