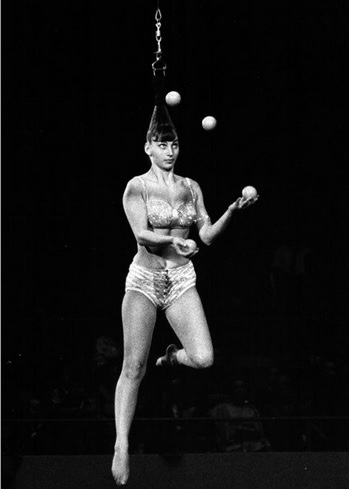

It’s like there’s a juggler on Jane’s right and a mime on her left, a talking parrot on her shoulder and a fire eater behind her. And humans can only process so much, so the circus crowds out the context our mind would normally fill in on its own.

*(This whole post is just looking at the part of Miss Bates that is a device. Because until Mrs. Elton comes to town she is that. But she’s also a wonderful character. My mea culpa for when I’m too harsh.)

Except for a few small peeks, Jane Fairfax must be hidden in plain sight. What a wonderful problem for Jane Austen to solve! Hallelujah. Because in creating this problem for herself, Jane Austen solved it with the most delightful plot device in the history of story: a little moving, talking circus called Miss Bates to follow her beloved Jane around. And Austen throws that circus tent up not only when Jane is on stage, but when other people are talking about or even thinking about Jane. Every time you try to see Jane, Miss Bates starts juggling.

Like, I know Jane Austen didn’t literally say, “I will write a circus, and I will call her Miss Bates,” but I am going to pretend that she did, and you can’t stop me.

The only way this story stays afloat is if Jane Fairfax stays blurred and unreal until Austen is ready for her. On the other hand, if we see too much of her and she’s simply the stiff, opaque statue that we get in her first interaction with Emma, then not only does her character cement itself into a form that is impossible to care about, but it also makes revealing a 3D personality later on implausible. She needs to be obscured and projected onto for a long time. The reveal must be careful. And credible.

We don’t get many words from Jane Fairfax. We mostly see other people talk about her, or forget about her beneath the constant flow of Miss Bates’ words. Everyone else can escape the flood of words, but Jane almost never can. Going through the book trying to look almost soley through the eyes and ears of Jane Fairfax makes Miss Bates’ constant chatter so different. It’s more interesting, for one, but mostly it’s more oppressive. Even when it’s funny. It’s very easy to forget Jane Fairfax on the page because she is rarely where the action is and Jane Austen keeps a virtual circus of distraction around her most of the time she is technically in a scene, but I honestly think anyone would crack in a week in her place.

The other thing that going through the book trying to look almost soley through the eyes and ears of Jane Fairfax does—did—for me, is it made me love her. I literally feel protective of a character in a novel.

“…but a blush, a quivering lip, a tear in the eye showed that it was felt beyond a laugh.”

POST: The Miss Bates Traveling, Talking Circus. CHAPTER BY CHAPTER

To see Jane, Miss Bates must be removed. Like at Emma’s dinner party. Or like at Donwell, escaped. Or like at Box Hill, silenced. You may notice the one common denominator that not only Emma’s friends, but our author, agrees with: Emma is the key to freeing—and seeing—Jane. (At least until Mrs. Churchill dies and the mask is fully ripped off.)

Note – Dec 14, 2023: The part about only Emma having the power to separate Jane from Miss Bates changes after the engagement reveal, but Austen’s rule that Jane must be separated from Miss Bates to *be* remains absolute and unbreakable throughout the book. Mr. and Mrs. Weston visit after they learn of the engagement, but Mrs.Weston has to go back with the carriage for Jane to open up.

…and, in the course of their drive, Mrs. Weston had, by gentle encouragement, overcome so much of her embarrassment, as to bring her to converse on the important subject. Apologies for her seemingly ungracious silence in their first reception…

“Emma” ❦ Chapter 48

And then Jane meets Emma in the stairwell, and is pretty feisty with Mrs. Elton in the apartment with Emma before Miss Bates comes home. Then Emma leaves and Jane follows her down again and we get a very nice moment between them. “Let us forgive each other at once. We must do whatever is to be done quickest, and I think our feelings will lose no time there.” And last, the meeting with Frank and Jane together at Randall’s.

It is only Emma who holds a position both of power and situation to easily enable her to have a party that Jane can come to alone. Emma is clearly the only person at Donwell whom Jane can rely on to tell everyone she’s left Donwell on her own—the only one who can aid Jane in her successful escape. (Poor Jane! Even that turns on her!) And finally, at Box Hill, Emma shuts Miss Bates up—propelling the tension, character development, and love story forward—but also enabling Jane the aural and mental space to face down Frank Churchill and calmly speak daggers to him, hitting her mark with every word.

Once you reverse engineer what Austen has done—or really, once you just start looking at it, there’s no engineering necessary—this suddenly unmissable thing you’ve somehow managed to miss almost seems like a magic trick that you’ve learned the secret to. And once the trick is revealed, if you’re like me you will marvel at the fact that Jane Austen not only pulls it off, but does it in such a way that we never even notice all the distractions she’s throwing at us. (Or at least marvel at the fact that we don’t recognize them as distractions.) The reveal of Jane is slow and mostly painful. “Poor Jane Fairfax,” indeed. But it is always completely believable. Although everything surrounding her character is totally contrived madness—the talking aunt, the fantasizing protagonist, the patronizing patroness—we don’t spot it as the distraction it is because every character is brilliant and believable on her own.

Miss Bates is a plot device—an aural blind to obscure Jane Fairfax —and an ingenious one. She provides a constant traveling circus, dazzling and distracting, and always keeping the reader from seeing Jane Fairfax. It won’t be until Emma does what she ought and effectually removes the blind by separating Jane from Miss Bates and inviting her to the dinner party alone that we will finally see this lovely young woman.

Miss Bates is the initial and biggest blind, but not the only blind. Austen sets up layers of distractions and distortions that she then filters Jane through. Emma’s reactions to “Jane” are the next filter, and because we are told by Emma that they are reactions to Jane it’s easy to miss that they’re almost entirely reactions to Miss Bates. And once you throw Emma’s own fantasies on top of all that—despite being confident as a reader that she’s getting things wrong—Jane is effectively buried. And that’s without even factoring in Frank Churchill.

But aside from being a blind, Miss Bates the character also distorts the actions of Jane Fairfax in the story: by keeping her stiff and silent and almost surely humiliated. Miss Bates’ nonstop talking, as well as her near-nonstop supplication and thankfulness to everyone around her changes Jane’s ability to interact normally. (And over time helps push Jane to the breaking point. It’s not about whether Miss Bates is a good person, it’s simply that being trapped with her constantly would be too much for practically anyone.)

Once Mrs. Elton comes to town, Miss Bates becomes more of a lens than a blind. But before that, she hides Jane from our sight. And after that, she still remains a pressure point on poor Jane.

It’s almost impossible to think about what Jane’s life is like when we first meet her—still seeing everything filtered through Emma—but the moment we back up and consider the situation Jane is in, even without the engagement, her actions and her “reserve” make total sense. (Especially considering that even the most outgoing characters have to work to break through Miss Bates’ monologues, and only Mr. Knightley manages to have any real success.)

By the time Emma has her dinner party and Jane is momentarily freed, she has, for a true love that she really believes in and is caught up in, willingly locked herself away in a tiny house with a woman who literally never shuts up, and is now constantly even accosted inside those tiny rooms (and everywhere else) by a stupid, horrible woman who hurls her very name as an insult and due to her talking aunt’s suffrage has taken over her whole life. Oh, and who also talks all the time. All that would be enough to break anybody, but on top of all that she is keeping a secret from everyone.

A most mortifying change

Think about the change Jane has endured. Before Mrs. Elton arrives, before even Frank arrives, she has gone from being seen and treated as an equal in “elegant society” to suddenly being the charity case, far away from her closest confidant and adopted sister, without the protection of Col. Campbell, living in a couple of small rooms, no one to talk to, and always, always assaulted by an inescapable and nonstop soundtrack of words, words, words. That she loves the person drowning her in those words may actually make it all more difficult to cope with.

For most of Jane’s life she has been used to relative luxury. Not royalty-level luxury, but luxury nonetheless. Everything in her surroundings was both genteel and gentle. A cushion of politeness and respect insulated her on all sides. In Jane’s London home they almost surely had a butler, she probably shared a lady’s maid with the former Miss Campbell, they associated with other wealthy people like Frank Churchill, and regardless of her future, in her daily life—in her every interaction—she was treated like a lady.

Living constantly with right-minded and well-informed people, her heart and understanding had received every advantage of discipline and culture; and Colonel Campbell’s residence being in London, every lighter talent had been done full justice to… sharing, as another daughter, in all the rational pleasures of an elegant society, and a judicious mixture of home and amusement…

As she visits every couple of years, Highbury isn’t a surprise to her, but for the first time since childhood she is going to have to really exist there, and that’s a different footing. (And her treatment in Highbury bears no resemblance to how she has lived her life up till now. She’s classed even by the Coles with “the less worthy” females, and like a servant, the Coles address her by her given name.)

Jane, Jane! What’s in a name? Mrs. Elton’s most unpardonable sin.

She must be so lonely, even after Frank does visit. She has no one to talk to—about serious subjects, true—but her daily discourse on unimportant topics has dried up, too. Her adopted family is far away, begging her to come to them and she can’t tell them the truth about why she can’t. If Emma made a space for her at Hartfield, just like she’s done for Harriet, Jane would have a place to be. Some quiet to just read a book or talk nonsense. But instead she’s cut off from everything and almost everyone, and all she can do, most of the time, is simply endure.

So with that wind up in mind—and before I start tracking The Blind—I want to skip ahead just the tiniest bit to that first scene where we see Jane Fairfax live and in person. The first time we actually witness her in a room with Emma, speaking and being spoken to. (I think of it as “the statue scene.”) Jane is flat. Stiff. But even as a statue she is a disappointment. We are curious. She’s been built up, Emma and Mr. Knightley have just been talking about—or disagreeing about—her and her visit the night before, and so when she actually shows up we’re practically leaning forward in our seats.

The anticlimax that is Jane Fairfax in this scene is practically epic.

The first words out of her mouth, on the heels of a great Austenism, don’t tell us much. It’s just a person politely and appropriately responding to a conversational prompt on a topic she has no reason to be invested in. She’s new. Miss Bates has been jabbering. Maybe Jane hasn’t been paying close attention. She’s not really part of the broader conversation and doesn’t know any of the players. Austen says something funny, and Jane’s response is slightly humorous for that reason. But she seems to be trying.

Basically, we need more.

“…Jane, you have never seen Mr. Elton!—no wonder that you have such a curiosity to see him.”

Jane’s curiosity did not appear of that absorbing nature as wholly to occupy her.

“No—I have never seen Mr. Elton,” she replied, starting on this appeal; “is he—is he a tall man?”

And we get more with her next response, but it’s more in the wrong direction. So ungratifying. So seemingly stiff.

“When I have seen Mr. Elton,” replied Jane, “I dare say I shall be interested—but I believe it requires that with me. And as it is some months since Miss Campbell married, the impression may be a little worn off.”

Of course Jane is “reserved” about Weymouth and Frank Churchill, because she’s got a secret. But what about the rest?

I want to grab a few Ellen quotes from the necessary Reading Jane Austen podcast, and it’s important to point out that I’m skipping a ton of context as well as Harriet’s comments for the simple fact that what Ellen is saying is also the impression I had at first. It turns out that it’s not true, but with everything going on—with the circus that Austen has thrown up around Jane Fairfax—I think it’s what almost everyone sees. It’s like there’s a juggler on Jane’s right and a mime on her left, a talking parrot on her shoulder and a fire eater behind her. And humans can only process so much, so the circus crowds out the context our mind would normally fill in on its own.

Reading Jane Austen podcast: S4/Ep7

8:03 – 09:07

ELLEN: …but in fact Emma was put off by the way Jane speaks… she tries to be open to Jane and Jane pulls the shutter down …

So let’s back up. Reset the scene.

Proud, reserved Jane is tagging along with her aunt to go thank Emma for the charity pork she has bestowed on them. I don’t think it’s a stretch to believe this is a humiliating position for Jane, or anybody, to be thrown into. Jane is smart and has an excellent, limber mind, so she understands how things are and can probably cope as well as anyone, but it doesn’t change the fact that no one would feel wholly comfortable in her shoes. She’s still dealing with the degrading shock to her system, she knows she’s going to be there at least three months, and Frank hasn’t arrived yet. She might or might not have some of the same competitive feelings with Emma that Emma has with her, but they’ve never been besties and charity from anyone else on earth would probably be more palatable than charity from Emma. It’s like being in high school and having to go to a food bank before Christmas versus having that popular girl you’ve known your whole life and who you’ll see in homeroom Monday bring a charity box to your door.

I want to hide under the carpet just thinking about it.

“So obliging”

And it’s not like Miss Bates’ gratitude is dignified and restrained. It’s not just the nonstop flood of words, it’s the extreme supplication. It has to be almost torture for Jane.

“I come quite over-powered. Such a beautiful hind-quarter of pork! You are too bountiful! …as my mother says, our friends are only too good to us. If ever there were people who, without having great wealth themselves, had every thing they could wish for, I am sure it is us. We may well say that ‘our lot is cast in a goodly heritage…’”

And we don’t have to project or presume to know how much Jane hates being the charity case. Despite it being fairly self-evident on its own, we know from Miss Bates’ extra-long narration in Chapter 27 that the only time Jane almost quarreled with her aunt was over her truthful admission to Mr. Knightley that they were almost out of apples.1 “[S]he almost quarrelled with me—No, I should not say quarrelled, for we never had a quarrel in our lives; but she was quite distressed that I had owned the apples were so nearly gone; she wished I had made him believe we had a great many left.”

Emma is the benefactor and Miss Fairfax the charity case. They are in Emma’s home. And I will add one last bit of context to Jane’s state of mind. (I am in an ongoing debate with myself about how much I should bring out in this scene, but I think this last detail is important to understanding this woman behind the layers of smokescreen before moving on to The Blind that hides her.) Because just this one single scene is enough to start to understand how well The Blind works and how brilliant it is. It’s almost too good, because even on successive reads it continues to work and we don’t notice—and don’t notice that we aren’t noticing—most of the general contextual matter we normally fill in instinctively with characters and scenes. And I must do Jane the justice of really seeing her before looking at the way she’s obscured. I like her and feel for her too much not to give her that first. I actually adore her.

So the last thing to know about Jane’s emotional state is that before they left the house she was already having trouble coping. Already wanting to escape. Already over-taxed. Already “wearied in spirits.” And we know this, of course, from Miss Bates.

“For it is not five minutes since I received Mrs. Cole’s note—no, it cannot be more than five—or at least ten—for I had got my bonnet and spencer on, just ready to come out—I was only gone down to speak to Patty again about the pork—Jane was standing in the passage—were not you, Jane?—for my mother was so afraid that we had not any salting-pan large enough. So I said I would go down and see, and Jane said, ‘Shall I go down instead? for I think you have a little cold, and Patty has been washing the kitchen.’—’Oh! my dear,’ said I—well, and just then came the note.

Jane was standing in the dark passage2 and jumped on an excuse to get away when the note about Mr. Elton came, and now she’s in the home of the person she would probably least like to feel like a charity case in front of while her aunt goes on and on. It is not an equal or friendly footing. In London they would be equals, but here she is in an awful position. An unnatural inferiority is imposed on her. One she doesn’t deserve and is probably railing against in her very soul. Whatever the bigger reality is, however Emma actually feels, Jane must feel—or at least fear—that Emma is not seeing her as an equal. In this situation it would be difficult, and perhaps impossible, to make Jane feel comfortable, welcomed, equal, and at ease. Anyone’s defenses would be on high alert. It’s just such a bad situation, such a mortifying scene, and the footing so unequal and humiliating that the best she and Emma can probably do is escape it unscathed.

So with Jane stripped naked emotionally, what friendly overture does Emma choose to make?

She challenges her charity-case guest on her silence—(of all things!)—by pointedly telling Jane that she will not be excused from having an opinion about two people she’s never met getting engaged.

“You are silent, Miss Fairfax—but I hope you mean to take an interest in this news. You, who have been hearing and seeing so much of late on these subjects, who must have been so deep in the business on Miss Campbell’s account—we shall not excuse your being indifferent about Mr. Elton and Miss Hawkins.”

Those words to Mr. Knightley would be fine, but to Jane in this moment they’re at least ungracious, and more like hostile. Therefore if Jane’s reply was meant as a veiled “screw you,” I’m good with that. I’ll take her side, as I always take the side of the underdog against the bully. Because Emma’s treatment of Jane here feels far more like bullying than it feels like trying to be friends.

“When I have seen Mr. Elton,” replied Jane, “I dare say I shall be interested—but I believe it requires that with me. And as it is some months since Miss Campbell married, the impression may be a little worn off.”

Suddenly, I think Jane handled it well.

And now that I’ve said all that, I realize tracking Jane and her personal circus must be a separate post. There’s a lot.

The Miss Bates Traveling, Talking Circus

You’ll never be able to unsee it.

- “…Mr. Knightley called one morning, and Jane was eating these apples, and we talked about them and said how much she enjoyed them, and he asked whether we were not got to the end of our stock… I could not absolutely say that we had a great many left… and I could not at all bear that he should be sending us more, so liberal as he had been already; and Jane said the same. And when he was gone, she almost quarrelled with me—No, I should not say quarrelled, for we never had a quarrel in our lives; but she was quite distressed that I had owned the apples were so nearly gone; she wished I had made him believe we had a great many left. ↩

- Bates narration, Chapter 27 ↩

3 Comments Add yours