“It could be they didn’t see much of each other in the summer of 1958.”

This whole thing just came pouring out of me Monday night when I limped over to Tumblr to cross-post my Delusional Lewisohn piece.

In “A BEATLE DIDN’T SAY THAT!” one of my examples was Lewisohn very designingly making it seem like Paul wasn’t around for John after Julia’s death using a combination of an altered quote from George Harrison’s mother and the contextual phrasing surrounding it. Many know of Mrs. Harrison reassuring George that she wasn’t going to die, but Lewisohn cunningly alters the rest of her words and his supporting sentences to make Paul seem unaffected and distant after John’s mother’s death, and to paint George and Paul both as relatively unconcerned, when what Louise Harrison specifically says is that she sent George around to John’s to bring him over so that he could play guitar together with Paul and George, and that “they always helped each other.” For Lewisohn to surgically alter the words that he does quote, chop off the rest, and then sew them back up with misleading insinuations to create not only a false—but opposite—impression of the boys’ closeness after John’s loss is unforgivable.

Come with me, and I’ll show you what I mean…

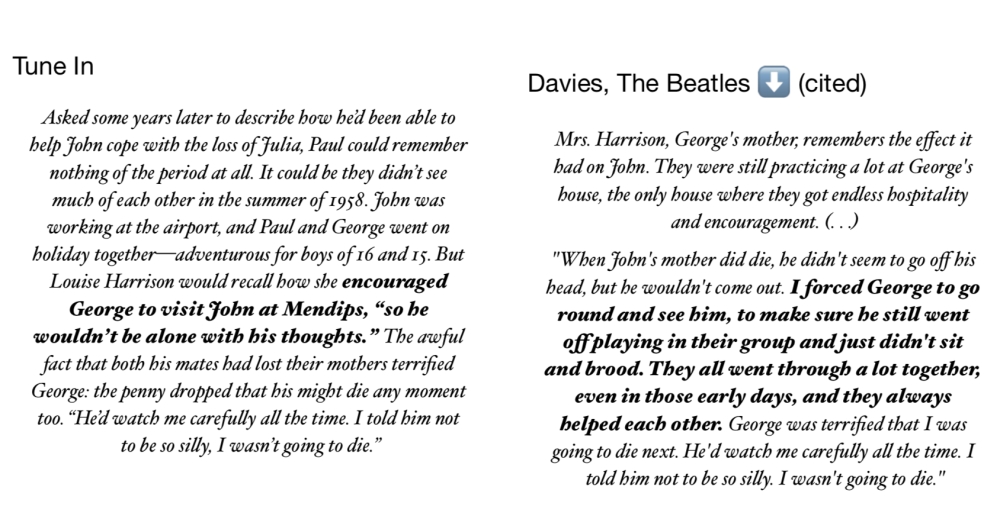

I’ll go through it step-by-step, but here’s both full quotes for comparison:

Davies: THE BEATLES >(cited–

Mrs. Harrison, George’s mother, remembers the effect it had on John. They were still practicing a lot at George’s house, the only house where they got endless hospitality and encouragement. (…) “When John’s mother did die, he didn’t seem to go off his head, but he wouldn’t come out. I forced George to go round and see him, to make sure he still went off playing in their group and just didn’t sit and brood. They all went through a lot together, even in those early days, and they always helped each other. George was terrified that I was going to die next. He’d watch me carefully all the time. I told him not to be so silly. I wasn’t going to die.”

–& twisted) >Lewisohn: TUNE IN

Asked some years later to describe how he’d been able to help John cope with the loss of Julia, Paul could remember nothing of the period at all. It could be they didn’t see much of each other in the summer of 1958. John was working at the airport, and Paul and George went on holiday together—adventurous for boys of 16 and 17. But Louise Harrison would recall how she encouraged George to visit John at Mendips, “so he wouldn’t be alone with his thoughts.” The awful fact that both his mates had lost their mothers terrified George: the penny dropped that his might die any moment too. “He’d watch me carefully all the time. I told him not to be so silly, I wasn’t going to die.”

Lewisohn doesn’t outright say that Paul wasn’t around when Julia died, but he strongly infers it—deceptively altering and truncating a supposed-Mrs. Harrison quote—turning George’s mom talking about how close the three were at that time and how they helped each other, into support for his knowingly false inference that Paul barely saw John after his mother died. Lewisohn then adds an introductory statement that makes it seem as if Paul was nowhere to be found, without actually saying that.

Observe how artfully he says it without actually saying it. Mark Lewisohn has perfected lawyer-speak narration.

Look at his first two sentences:

Asked some years later to describe how he’d been able to help John cope with the loss of Julia, Paul could remember nothing of the period at all. It could be they didn’t see much of each other in the summer of 1958.

But we know the secret. We know what Mrs. Harrison actually said. And so does Mark Lewisohn, by the way.

Lewisohn tells us that someone, somewhere, “some years later” asked Paul this “question” that I literally cannot even comfortably end with a question mark:

“Paul, describe how you were able to help John cope with the loss of Julia?”

Really?

I’m not going to lie, I do not believe that anyone ever asked Paul McCartney that idiotic question, but even if we give Lewisohn the benefit of the doubt— **excuse me i can’t stop laughing. one sec**

—even if we give Lewisohn the benefit of the doubt that someone, somewhere, at some unnamed time, asked Paul to describe how he was able to help John cope with the loss of Julia, just what exactly would we expect Paul McCartney’s answer to that to be? Honestly, try to imagine the look on Paul’s face if he was asked to describe how he helped John to cope after Julia’s death.

“Paul could remember nothing of the period at all.”

Did an appellate lawyer write this? No, this is contract law genius. I can find the holes in almost any contract, and Lewisohn’s own words around a misused quote are a work of legal art. He never quite says what you think he said.

But on the quotes, themselves, Lewisohn swings for the fences. He is without shame or fear. He has no qualms about putting quotation marks around any old thing he wants to say. One cannot go too many pages without finding something that shocks the conscience.

These are not “mistakes.” They are a very deliberate cutting and pasting together of historical figures’ words to make them mean something different—and often opposed to—what the speaker intended. He then surrounds the misquotes with carefully worded insinuations that don’t really say what you thought they did.

THE ACTUAL MRS. HARRISON QUOTE

Hunter Davies—our source—was very good at weaving information-heavy exposition together with the quotes from his interviews, and since he interviewed everyone himself, he can tell us a lot in his own words.

What that does for you and me is that we get the context from the guy who asked the questions and spent time with these people, and that makes it a lot harder to get away with using these quotes out of context. Like, before we even get to the direct quote from George’s mom, Davies is telling us what she remembers from the time. And it’s a lot. Because that’s when the boys practiced at the Harrisons’ almost every day. And it’s awesome because her memories almost always include what the boys were eating at the time. (Seriously.) Like, she’d “given them all beans and toast” a few months before Julia died when John said to Paul, “I don’t know how you can sit there and act normal with your mother dead. If anything like that happened to me, I’d go off me head.”

Davies also calls Mrs. Harrison “one of nature’s ravers.” 🥹

Everyone seems to agree that during this time the three were always at the Harrisons, and it’s certainly the picture we get from Mrs. Harrison.

Davies is telling us all this, and leads into her direct quote by telling us what she “remembers.” (So this is what Lewisohn knows before he lifts and shifts the quote and re-sews it into his text with his own exposition.)

“Mrs. Harrison, George’s mother, remembers the effect it had on John. They were still practicing a lot at George’s house, the only house where they got endless hospitality and encouragement.”

And I trust Mrs. Harrison’s memory because I am a mom, and I remember every trauma of my children’s friends because I was the local Mrs. Harrison. We love those kids with all our hearts and they’re so connected to our own kids that nothing happens to one without all of them feeling it. And the mom is seeing it all, every day. So how do we need Paul’s answer to “Describe how you were able to help John cope with the loss of Julia?” when Mrs. Harrison has twenty stories, all with corresponding menus?

And Mrs. Harrison is saying that she sent George to get John out of his house so they could all play guitars together “in their group.” Not, where was Paul? No one knew where Paul was so I sent George to visit John at Mendips and Paul wasn’t there either.

Where’s Paul? Who could possibly know? “It could be they didn’t see much of each other”—but could it? It could be that Paul went ice skating in Sweden, EXCEPT HE FUCKING DIDN’T. Why are you lying to me in legalese in a Beatles biography?

(He’s just asking questions.)

“But Louise Harrison would recall how she encouraged George to visit John at Mendips” isn’t true, but also isn’t sane. If you pause and put as much thought into each sentence as was spent constructing them, you notice how many of them are patently ludicrous. Mrs. Harrison didn’t encourage George to “visit” at Mendips because no child “visited” at Mendips. What are you even saying? To keep Paul and John away from each other you’re talking nonsense. Visit? At Mendips? I can just picture John, Mimi and George sitting around having tea. But also, Mr. Lewisohn, those are not words that Mrs. Harrison said, and in fact, those words mean something completely different than the words she did say.

What she said was she sent George over there “to make sure he still went off playing in their group and just didn’t sit and brood.”

And Nature’s Raver Mom would see John not showing up like usual and would send her son out to make sure John knew he was wanted, and give him a little kick if necessary. She would want him in her house so she could feed him and make sure he was okay and to give him the comfort of playing music together with his friends.

They’re the Beatles, and they got through it together, playing music. That’s the real story, the true story, and a much better story.

And then she says “they all went through a lot together, even in those days, and they always helped each other.”

That’s what Mark Lewisohn cut out so he could speculate to us that maybe they didn’t see each other much. If that’s not purposefully deceptive then words are meaningless. There is simply no other rational inference. None.

(I have tripled my website post now. I regret nothing.)

Let’s take this baby home.

Because Mark Lewisohn completes the picture of John alone and ignored by George and Paul, and he does it by sneaking his own words into the mouth of George Harrison’s dead mother.

I want to pause a moment to let it sink in.

Mark Lewisohn changes Mrs. Harrison’s actual words from “sit and brood” into “alone with his thoughts,” which further emphasizes the absolute absence of Paul and George. But he knows that John was not alone because he replaced Mrs. Harrison’s words that said they were together playing music with his own words of John all alone. It almost sounds like Paul and George spent the entire summer off hitchhiking, completely unaffected by John’s pain when John needed them most, contrasted with a conjured parallel image of a traumatized John left separate and alone. (Except for his inner world.)

But John wasn’t alone that summer. We know that from all of them, and we know that from the unaltered words of Mrs. Harrison, the nurturer of these three shaken and heartbroken boys.

–

(I had added this last bit before I noticed on May 25, 2024.)

–

And it’s worth taking a second to think about Mrs. Harrison telling us that John had told Paul he’d go off his head if his mom died (while they were eating beans and toast.) That gives us a window into the three boys around this time, and some insight into how open they were with each other. I don’t think anyone believes they were having deep conversations about feelings, but they also didn’t pretend their tragedies didn’t happen. They were incorporating their tragedies into their shared reality in their own brotherly ways, and they were comforting each other in the way families comfort each other: by being together. And for these three that meant playing music together, a form of communication that often makes words seem like coarse, clumsy objects. (If you have ever even harmonized with someone you understand this. Simply singing an a cappella harmony with one other person is enough to understand that weird, electric connection, and no one did harmony better than the Beatles.)

These boys were the best, best, best of friends and they knew each other intimately because they played music together. That was their communication. That was their magic. That was their bond. From the start, to the end. We’ve all seen it. Even at the end, when they were making music they transformed into a new thing, and that thing was so unique that it still mystifies and charms us. There was something pure and good in it. Somehow—and I don’t want to sound too corny but we all know it’s true—there was love in it. And no matter what else happened or how mad they got, they still stayed connected and worried about each other for the rest of their lives. They all knew that as long as they lived, no one would know them like they knew each other, because they went through so much together, and they got through it all and got closer through it all by making music together.

Of course they felt it. Of course they were worried about John. They loved each other and this was like a bomb going off in their little world. And for John, knowing that Paul—who can be quite nurturing—could really truly understand must have been the biggest comfort of his life. And just ask yourself, if it had been Mrs. Harrison instead of Julia, do you imagine they would not all be devastated and brokenhearted for George? That they wouldn’t care? It would be worst for George of course, but it would gut them all, and George’s two best friends would be incredibly hurt for their friend. Either George and Paul had no hearts—or—George and Paul weren’t really John’s friends—or—George and Paul felt John’s pain. John losing Julia was formative and bonding for all three of them, but as we know, especially for John and Paul. They were the only two people in their world who could understand what the other was going through.

We know how much the Beatles loved each other and some of us understand the kind of bond playing music together creates. When you are that close and connected none of you suffers alone. George being afraid his mum might die actually shows that. Unless they were mildly sociopathic this must have been an incredibly intense and traumatic moment for them all, and that they had each other is what turned them into the family the world met in 1962. Every description of them after this point says they were always together, that they spoke their own language and seemed to inhabit their own wavelength. In Hamburg, at the Cavern, in Scotland…. literally always. Why would it be any different during this summer? And Mrs. Harrison told us just that, she told us that they were there for each other. She told us that those three guys who we know—those three guys who were so close that their connection made its own kind of magic—that those three guys didn’t suddenly stop being those three guys in the summer of 1958.

Comment:

I completely missed the implications of this, which is that Paul basically abandoned John in his time of need, when I read Tune In, even though it should have jumped out at me. Given that both John and Paul both said at various times that Julia’s death bonded the two of them together even more, since they now had the loss of their mothers as another thing they had in common, it’s unlikely that John would have trusted Paul if Paul hadn’t been there for him. I’m not discounting George’s role in this (he was very supportive of John), but George isn’t the one who’s being portrayed in a highly unflattering light.

My reply:

He’s very good and so it’s easy to miss. He’s trying to shift our mental pictures and feelings on the closeness that bonded Paul and John—and as you say, that we know from their own mouths bonded them—but without outright lying. So much of the book is like this. Once you take it apart it is so patently contrived and cunning that it becomes impossible to see as just honest mistakes of phrasing. It’s scalpel work.

(Both in this reblog ↓︎ )

2 Comments

Comments are closed.