“One of the things about this book that is a strength is it’s not me saying anything, it’s them or other people. I shape the text, I plot where it goes, I weave it, but the quotes are theirs. And so when I’ve got Paul McCartney behaving in a way some readers might think, ‘Whatever, oh dear,’ it’s actually him saying it. So you end up thinking that to his own credit he said that. It’s not me saying it.”

—Mark Lewisohn, ‘Noted,’ (October 7, 2013) Somerset, Guy. The Mark Lewisohn Interview

Dr. Frankenquote

A lot of people for a long time have put a lot of trust in Mark Lewisohn’s footnotes. Or at least in the fact of those footnotes. Because once you dig through them for any length of time you quickly discover that Mark Lewisohn’s footnotes hold secrets that would get him expelled from any undergraduate program. They reveal a “history” contrived through a mass of Frankenquotes, ala carte creations, Lewisohn rephrased ‘paraphrases,’ and worse. For some parts of the narrative things aren’t too bad, while in others monsters lurk around every corner. But this is not the sort of thing that’s graded on a curve, and it is past time to have a conversation about what standards should be accepted in Beatles’ scholarship.

Lewisohn lists his sources unlike most others. And his footnotes alone are more insightful than some other writers’ books.

Reddit, in r/beatles

I do not judge footnotes based on their insightfulness, nor do I want to single out a redditor, but I grabbed the comment because it’s an opinion that is widely shared and even accepted as canon. At least by people who have not combed those freakish footnotes. And while the pages of piled up sources do look fearsome en masse, a closer inspection reveals an offense to the truth, a threat to the record, and a blight on Beatles’ historiography.

“The rules for writing history are obvious. Who does not perceive that its chief law is never to dare say anything false, and never dare withhold anything true? The slightest suspicion of hatred or favor must be avoided. That such should be the foundations is known to all; the materials with which the building will be raised consist of facts and words.”

–Cicero

A Look at Lewisohn’s Monsters

First, what are quotes? And why are quotes?

Quotes are the soul and center of recorded history.

And the rules around quotes and quotation marks are pretty simple. Most people, even if they’ve never written anything beyond a term paper, understand what quotation marks represent.

A set of quotation marks means, “This person said or wrote ‘these exact words’ at this specific time.” You can smash a quote from two hours before or two years before right up against a separate quote to make your point—although it might get your grade lowered—but what you cannot do is take two different statements from two different times and make them seem like they are one statement.

When you put words inside one set of quotation marks you are stating, in black and white, that the identified person made this statement. That they said all those words together—or if you want to excise a reasonable part and use ellipses to represent that— as part of the same statement.

Look, combining two separate quotes that are not part of the same thought or topic is not a subjective issue. It is not an issue of controversy. Quotes are the bone marrow of written history. Quotes are the alpha and omega. In academic work or journalism they have to be, which makes sense as soon as you think about it. If it was cool for me to take a transcript and grab half a sentence from page 2 and half a sentence from page 17, push them together as if those words were spoken one after the other in a single thought, I bet I can manage to get those words to say almost anything I want.

Separate thoughts must be in two separate quotation marks. Separate. Somewhere between four sentences and a paragraph is widely accepted as the “two separate quotes” line, and there can be some ethical and technical wiggle room in a long rant by a person, but what makes all that subjective nonsense go out the window is if the quotes come from two separate questions. Or two separate days. That’s two quotes. Not hard.

Which again, makes sense if the point is conveying information to the reader and lessening the chance of a writer manipulating someone else’s words to express something that the person didn’t mean.

This is the contract inherent in a quote. These are the rules we all agree to and understand, and these are the reasons why. And there’s no reason to break them.

Why do you want me to believe that John said these two things at one time? What was wrong with what he did say?

The five most common ways Mark Lewisohn mauls the meaning of the quote:

The basic LEWISOHN Frankenquote 🧟♂️

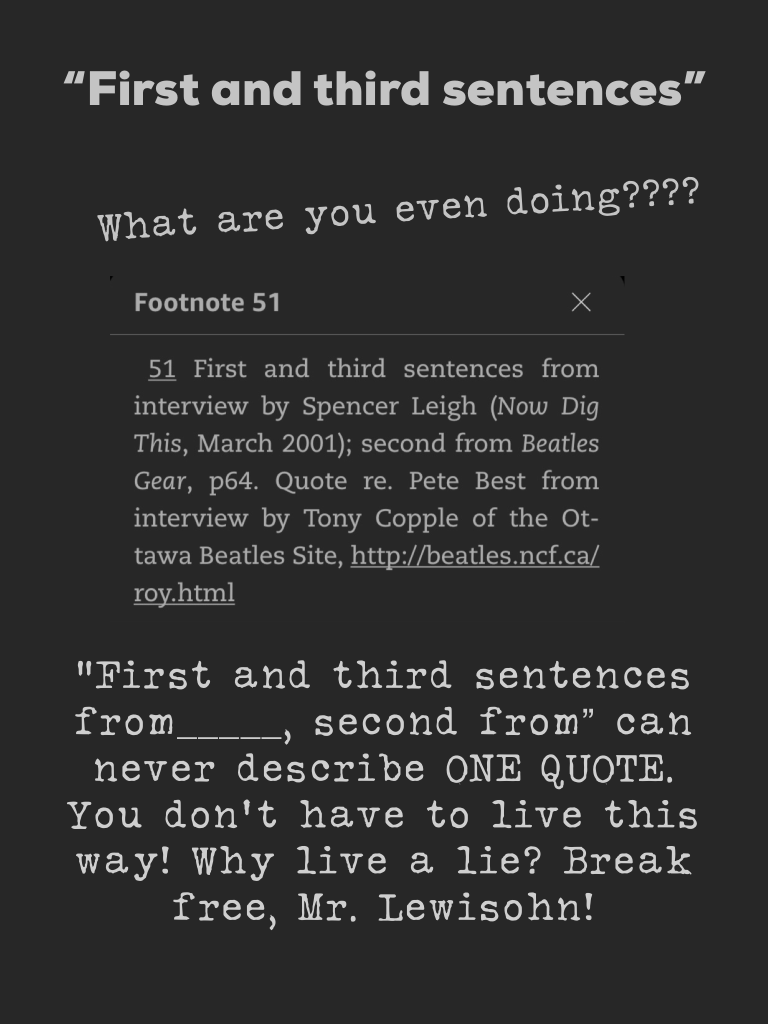

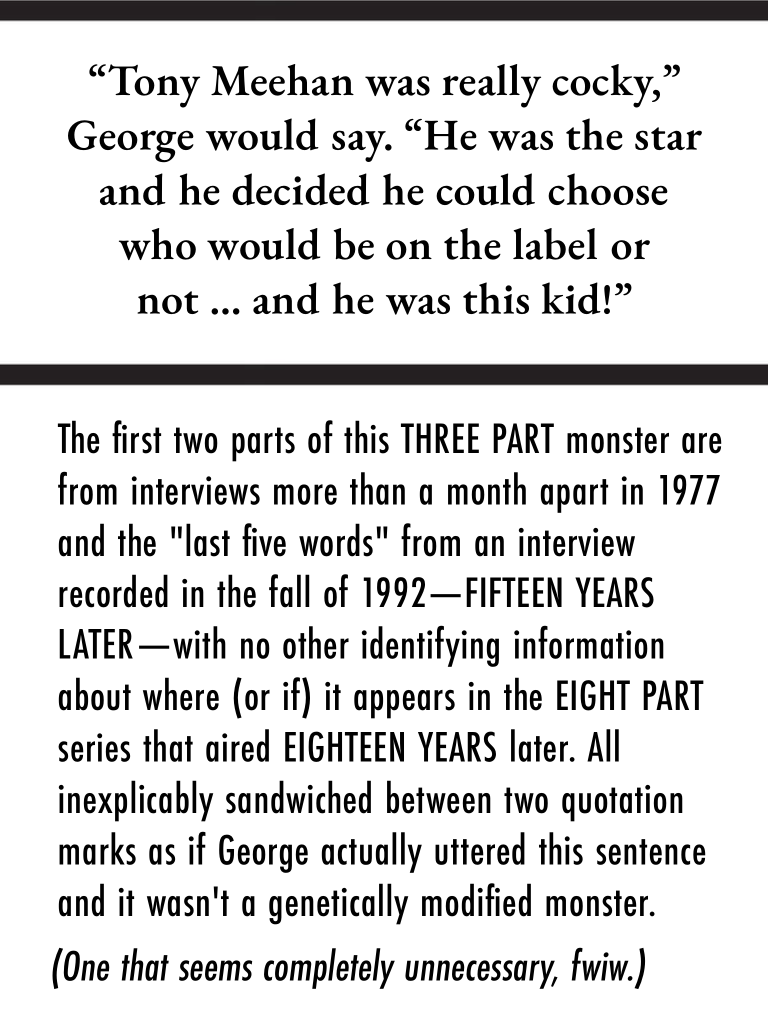

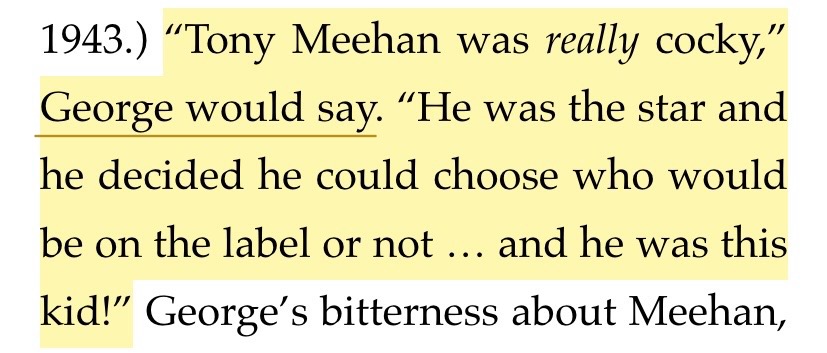

This three-headed monster attributed to George Harrison is a very dull little guy. Not particularly venomous. Just convenient, I guess. For whatever reason, Mark Lewisohn decided it was worth rummaging through the quote buffet until he collected enough pieces for George Harrison to say this thing. “…concluding five words from…” What are we even doing here? No, really. Please tell me.

And like a lot of the footnotes for these bespoke quotations, there are further problems. “[F]rom interview for Beatles Anthology”? An interview that aired? In one of the episodes? Can you narrow it down? I guess I’ll just have to listen very closely to them all and hope I don’t miss the five words.

But if we got bogged down in the sorts of trivial details that would immediately lose a college student a letter grade off a History 101 paper we would never get anywhere. We have to stick to the violent felonies.

“George would say—” Would he? A Beatle never said that. Incredibly cavalier about a Beatle’s words.

These sorts of reconstituted, lab-engineered, made up “quotes” are shot throughout Tune In. “Quotes” made up of words from two, three, and even four sources, spoken months or often years apart.

Ala carte creations 🍱

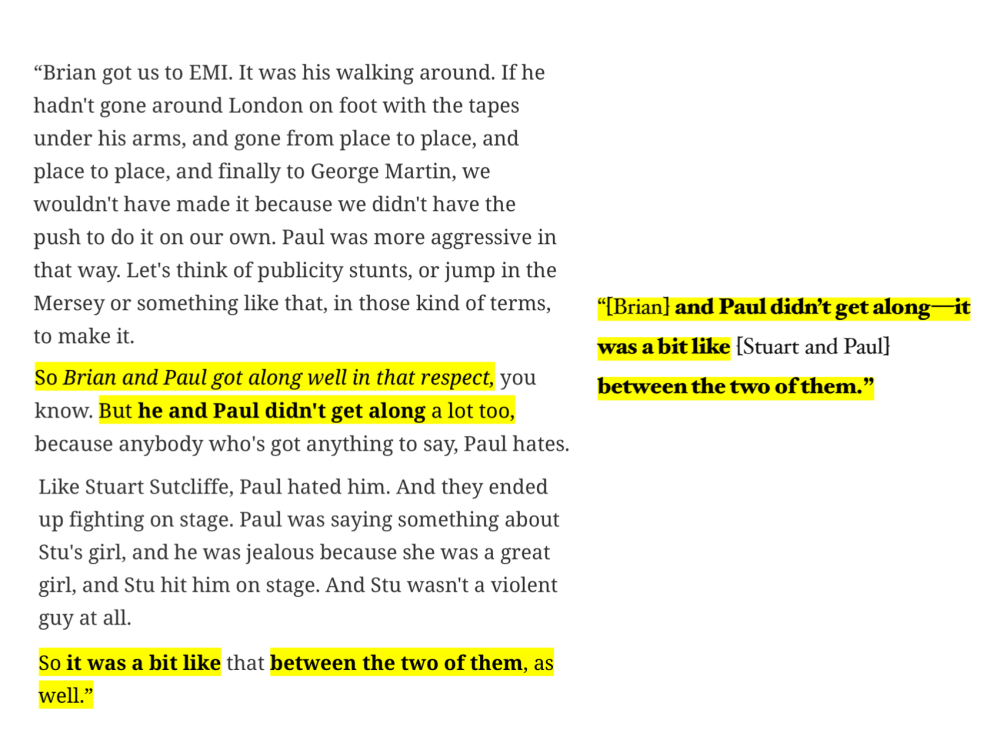

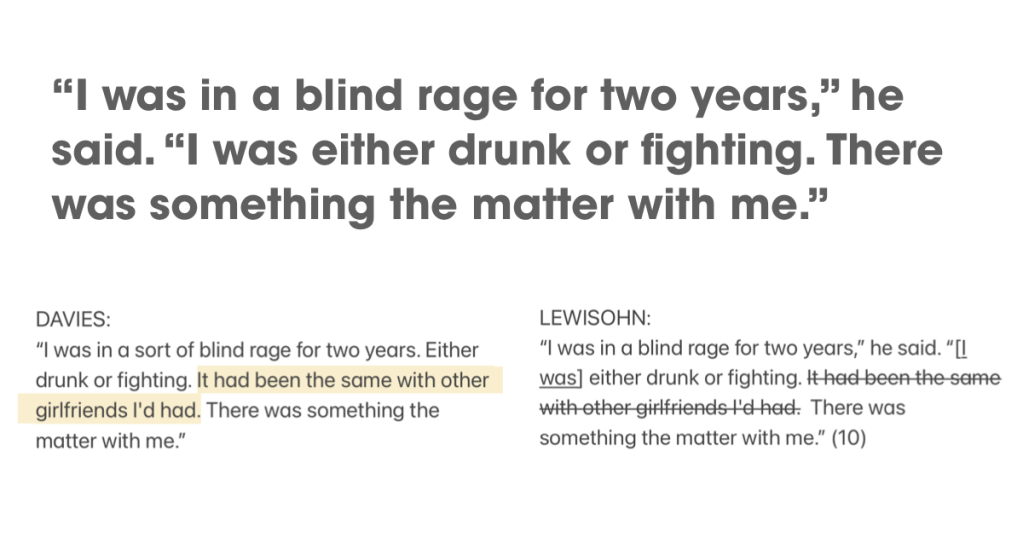

These ala carte creations come in all shapes and sizes. They might just be words that have been plucked up and glued back together to make something more useful to a particular narrative. (Ellipses or dash optional.)

THE Donut 🍩

Then there are a seemingly uncountable number of “quotes” with a sentence or three ripped out from the middle, but with zero representation that more words were ever there. (And in most of these particular deceptions, the simple representation of something excised (. . .) would make the quote fine. There are a lot of these, but they are also the easiest to fix.)

Buffet Bonanzas 🥡

Words lifted and twisted beyond recognition until they say something brand spanking new.

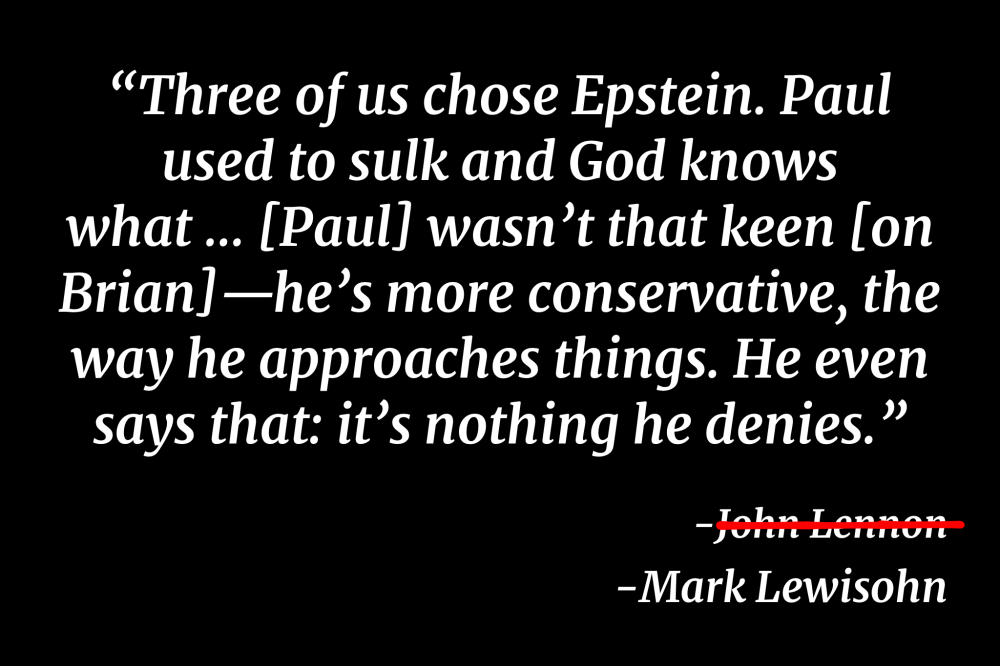

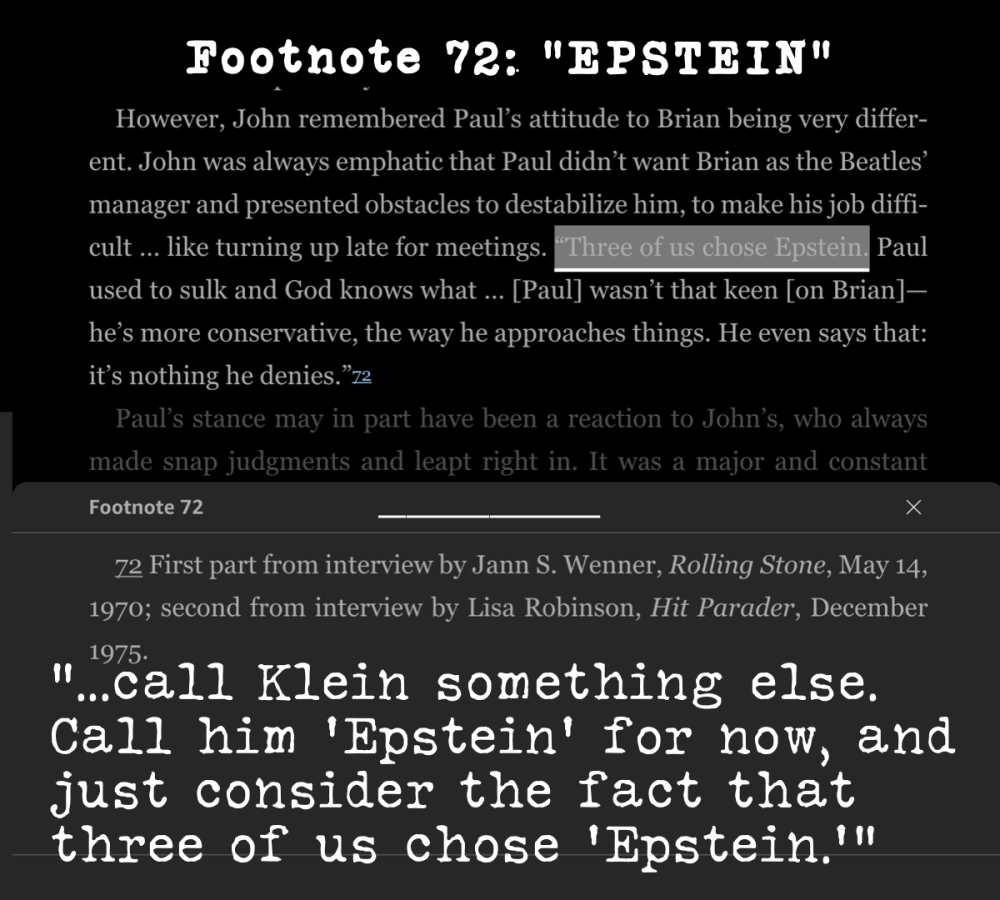

“I don’t care what you think of Klein, call Klein something else. Call him ‘Epstein’ for now, and just consider the fact that three of us chose ‘Epstein.’”

John Lennon to Jann Wenner, Rolling Stone, May 14, 1970

(Half of Footnote 72)

However, John remembered Paul’s attitude to Brian being very different. John was always emphatic that Paul didn’t want Brian as the Beatles’ manager and presented obstacles to destabilize him, to make his job difficult … like turning up late for meetings. “Three of us chose Epstein. Paul used to sulk and God knows what … [Paul] wasn’t that keen [on Brian]—he’s more conservative, the way he approaches things. He even says that: it’s nothing he denies.”

(IT’S ALIVE)

The Lewisohn Remixes 🍸

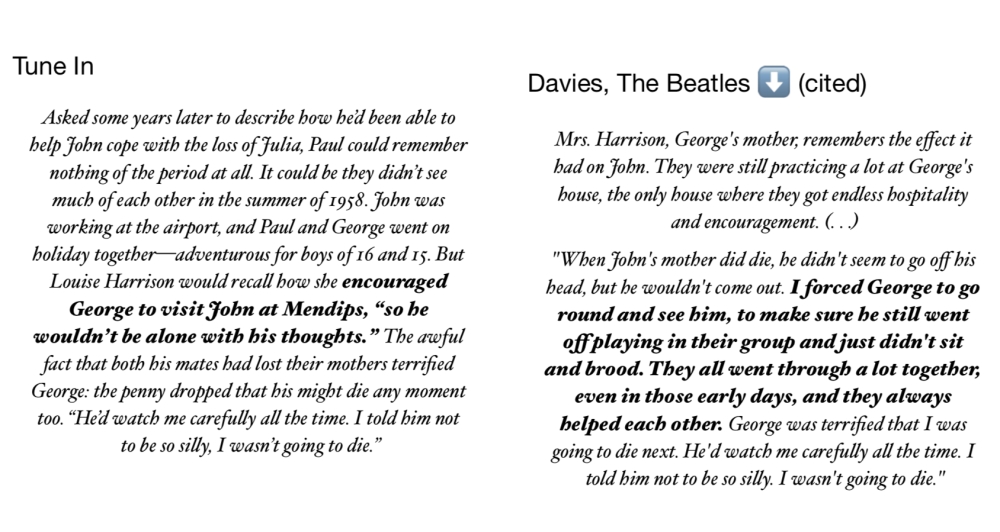

And then there are the “paraphrases.” I couldn’t even begin to guess how many of these there are, and often they aren’t even paraphrases, but whole new Mark Lewisohn re-interpretations with quotation marks slapped around them. But if you don’t check, you probably won’t know, because like this Lewisohn rewrite of a well-known Mrs. Harrison quote, there’s a good chance you’ll recognize the bulk of it, making it less likely that you’ll catch the scalpel work excising Paul. And while I don’t want to get caught in the nooks and crannies of intent in an example like this one I have to say, just this once, that what has to be a purposeful excising of Paul to create a slightly new quote on one side, combined with a badly acted, bad faith—(or bad scholar)—“Where was Paul when John’s mom died?” on the other, is par for the course.

Why do you have to slice and dice and reconstitute people’s words? No writer, and certainly no historian, should ever feel empowered to take words from a historical figure from two or three different places and topics and times, splice them together, and tell us, “Winston Churchill said this.” No he didn’t! Why are you so intent on changing the words of the people you’re writing about? What’s wrong with just using two different quotes?

You cannot take two or three quotes from two or three or even four separate statements, stick them between one set of quotation marks and say John or Paul or George or Joe Smith said this.

No they didn’t. They never said that. Why do you want me to think they did??

All these words are Abraham Lincoln’s, but this is not a Lincoln quote:

“Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of — making a most discreditable exhibition of myself.”

NOT an Abraham Lincoln quote, despite Lincoln writing all those words.

(I kept it ridiculous, although I didn’t have to.)

But I want you, the reader, to be saying to yourself, “Okay, enough already. I get it!” Because in the last few days I have wandered too far into the weeds too many times and written far too many words detailing the multiplicity of ways Mr. Lewisohn does violence to each and every law of reporting historical facts, and could write many more. And I will post a more detailed list of the crimes against the quote that I am charging Mark Lewisohn with as we go forward, but I don’t think we need that now. The fact is that every fair-minded person knows what quotation marks represent, and there is no more fair-minded group of people than serious Beatles fans and scholars. And it is those fair-minded scholars who I want most to hear me. Whether you’ve written books or host a podcast or just know that you know a whole lot of stuff and take seriously your part of the trust in preserving the truth about The Beatles for us and future generations, it is you I am really talking to. My Cicero quoting-freaks. The ones who care about getting it right.

“The chief, the only, aim of style is to put facts in a clear light, with no concealment.”

— Lucian of Samosata

What footnotes can do, and what footnotes can’t.

You can list multiple sources in a single footnote. That’s not only fine, it’s correct. If I want to tell part of a story based on several sources, that often means several sources in a footnote. But not for one, single quote. The problem isn’t the footnote, it’s the bioengineered quote on the page that you swept under a footnote hoping I wouldn’t notice.

Which leads us to what a footnote is not. A footnote is not a post-hoc fixative for your textual sins. You cannot do whatever you want as long as you confess it in a footnote. A footnote is not a magic spell. A footnote is not the universally understood symbol for “I have my fingers crossed behind my back.” You cannot fix lies and misrepresentations in the footnotes. Footnotes aren’t for trying to chase down three different sources to match up which part of a manufactured “quote” someone said on which date. Footnotes are not the picture on the front of a puzzle box. I should not need to find corner pieces to figure out which of these George Harrison words were actually spoken together.

Footnotes are a truthful and independently verifiable record of primary sources. It’s that simple.

And taking Mark Lewisohn completely out of the picture for a moment, I feel sure we can all agree that neither John Lennon nor Paul McCartney nor George Harrison nor Ritchie Starkey would want anyone rearranging their words as if they were guitar chords. You wouldn’t take three-quarters of Penny Lane and one-quarter of Across the Universe, put them together and call it a Beatles‘ song. So don’t take three quarters of John to Jann Wenner and one-quarter of John to Lisa Robinson, put them together and call it a Beatle’s quote.

My personal standard is that If someone represents, “A Beatle said this,” it better damn well be something a Beatle said.

None of the Beatles, dead or alive, would be cool with their words being taken out of context at all, let alone two or three different statements on god knows what being combined into one. This isn’t hard, though. Use two or three separate quotation marks, and don’t take statements out of context. Don’t mix and match their words, but don’t twist them, either. If a person said something, it is the historian’s duty to represent those words to the best of your ability, and then use them to tell a factual story focused on what you feel is important. Staying true to the original words and true to their meaning. If you can’t use those words without twisting them, then change your story to fit their words, not the other way around. If their statement helps tell the story your way, use it! For goodness sake, John Lennon said at least two opposing things about almost every topic on earth, so there should be enough to choose from without being deceptive. I actually want the truth. Don’t you?

Biography is story based around accurately represented, trustworthy and verifiable facts. And look, Beatles fans, whoever your favorite is: we are not going to get the truth about his history if we don’t learn to take these things seriously. Let’s have—if not high standards—at least the lowest generally accepted standards. In the mid-term we need a lot more Beatles scholars with a lot more points of view, and now—right now—we need experienced Beatles scholars to prioritize searching out and finding smart, interested people to mentor. And we simply must ensure that we aren’t allowing to solidify into stone “facts” that are not facts and statements no one ever made. I don’t think any honest Beatles fan—(which rounds up to all of them)—wants any question around that issue.

“Truth is for history what eyes are for animals. Remove the eyes of animals, they become useless; remove truth from history, it is no longer of any use. Whether friends or foes be in question, we must only follow justice.”

–Polybius

The record is the most important thing. Now, and always. This is not about John versus Paul. John versus Paul may always live in our hearts, but for Beatles history, it’s the wrong question. I’d rather someone be up front about their loves, but in the end the focus should be on representing the primary facts in their most pristine form. Love who you love most, but place truth above all. Pristine facts. Pristine quotes. Nothing hidden. Nothing misrepresented.

Let the historical actors speak for themselves. That is their right.

And the historian’s duty.

“…the materials with which the building will be raised consist of facts and words.”

will

LikeLike

will mark lewisohn be formally presented with these journalistic charges, and is he expected to respond? is it this flurry of important objections to his research and documentation in Tune In (part 1) that’s likely causing the 11 year span between the last publication and the long awaited Volume 2?

LikeLike